January 07, 2022

- Gartner client? Log in for personalized search results.

Why Do Executives Move Forward With Strategic Initiatives Even When They See Pitfalls Ahead?

Contributor: Marc Kelly

Executives bemoan the slow pace of business change, yet nearly two-thirds of those who head transformational initiatives tell us that half (or more) of the issues causing hold-ups were no surprise when they arose. Why do teams allow so many known sources of disruption into their projects? In a word, overconfidence. They believe they can course-correct their way out of trouble when they fall into predictable traps. But they are wrong.

Over 70% of initiative leaders said their top reason for moving forward despite the risk of delays was faith that they were nimble enough to handle whatever might come up, such as stakeholder conflict or resource logjams. But despite the belief in their, or their company’s ability, these leaders faced as much initiative-crippling drag as others. This held true regardless of the rigor applied to upfront planning or performance management practices.

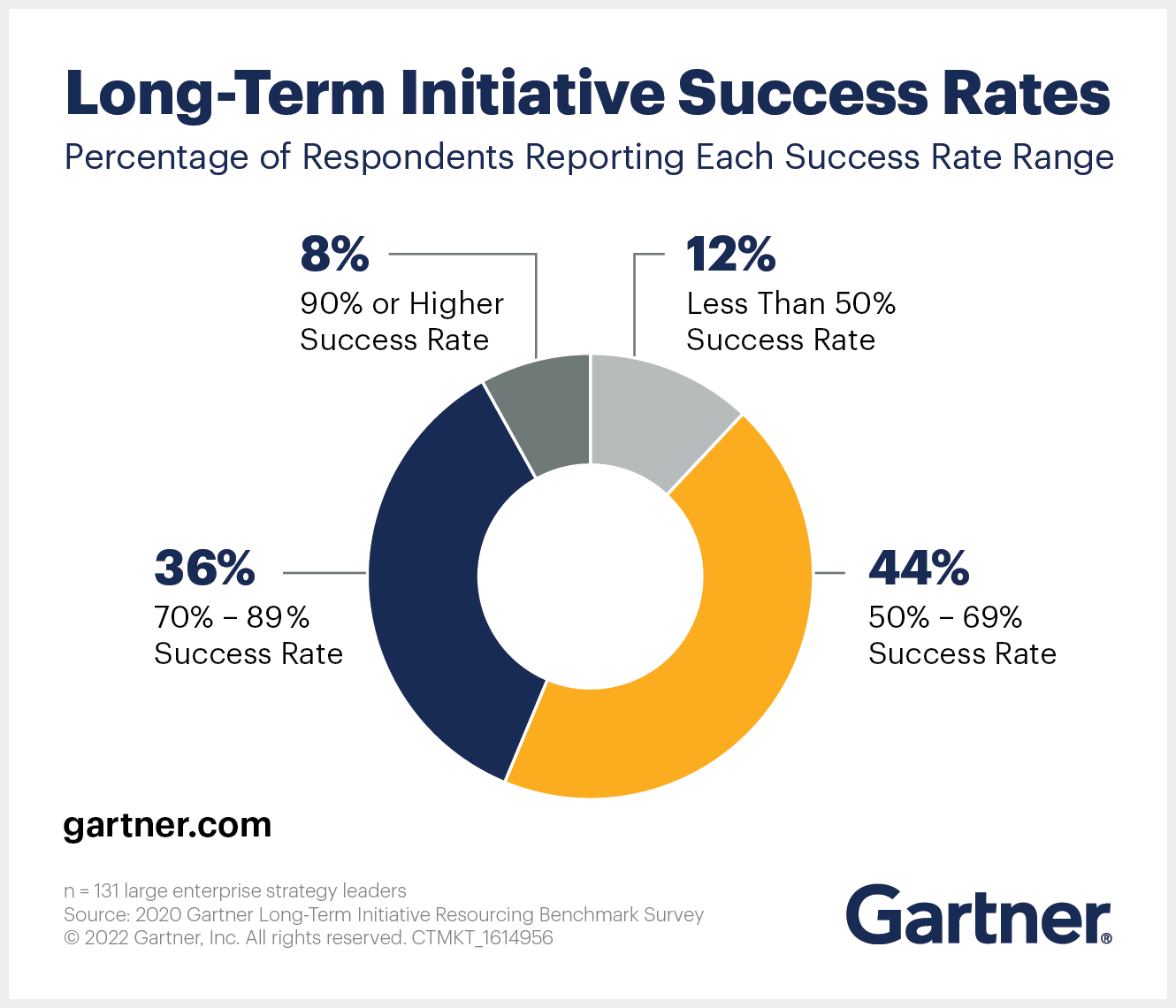

The issues that can delay initiatives, well known and recognizable as they are, reduce the odds of success down to barely better than a coin flip.

Download now: 3 Strategic Actions for Success in 2022

When Nimbleness Isn’t Enough

When asked why initiative drag was greater than anticipated, initiative leaders predictably cited a number of coordination challenges such as stakeholders downplaying conflicts, input being misinterpreted and individual impact on business partners. These issues outnumber other reasons for reported project problems.

With coordination being such an obvious point of contention, companies have rushed to increase stakeholder inputs, develop more governance bodies and increase initiative oversight. Initiative and/or business flexibility then becomes the main focus as business leaders attempt to rearrange processes, resources and decision rights to bolster initiatives’ chances of success.

On the face of it, this seems like a winning approach, and it is replicated across numerous companies. But the results are hard to isolate. A careful look at the relationship between a company or project team’s coordination and the ability to reduce execution drag on long-term initiatives reveals no significant impact. Those who believed themselves nimble enough to elude major hang-ups were just as likely to experience execution challenges than all other respondents.

When expected relationships between coordination efforts and the drag experienced by an initiative start to break down, it becomes more likely that coordination is only a symptom of a deeper issue. It’s likely flat out compatibility issues between what organizations are trying to do and what they do now.

The True Cause: Business Model Incompatibility

The U.S. healthcare system epitomizes the misalignment between new capability development and current business models. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital systems scrambled to introduce telehealth to safely treat patients for issues where an initial in-person visit wasn’t necessary. It took the novel coronavirus to shift this offering from “nice to have sometime in the future” to “critical immediate necessity.” The problem is that what feels like an incremental, customer-facing option results in significant business model problems.

Most integrated healthcare systems center their business models on total patient care. After an initial visit, hospitals rely on patients who need additional treatment or diagnostics to complete those at the same facility. A patient who initially visits a provider’s physician for shoulder pain, for example, might then head down the hall for an MRI or X-ray. But with remote visits, there is a greater chance that, instead of visiting the hospital of their primary care doctor, patients will visit another provider at a more convenient location. (This approach is only made easier by electronic health record sharing.)

With two models coexisting this way — in-person and virtual visits — one of three possibilities will unfold:

- The company will adjust its legacy business model to incorporate the new reality of virtual care.

- The company will strike a compromise and manage the two systems simultaneously, accepting the inefficiency caused by a stream of virtual care appointments.

- The virtual channel will be starved and begin to decline once the company’s focus on driving performance wanes.

For a strategic initiative like telehealth, the second and third scenarios lead to outcomes that range from mild dissatisfaction to complete disappointment. In all cases, however, progress against company objectives is sure to feel very slow.

Given the pace of change, most organizations will have plenty of opportunities to experience business model tension similar to the healthcare industry’s dilemma. In response to shifts in their own industries, many companies are executing more large-scale, cross-enterprise initiatives; they are pushing decision making further down into the organization while accelerating digital investments.

Take Two Deep Dives Before You Plunge Ahead

For initiatives designed to push the edges of a company’s business model, it can be hard to determine at what point they flex the business so far that no amount of agility will save it. To facilitate their planning, companies should probe for two markers of the outer limits of flexibility.

1. Patterns of Past Initiative Success and Failure

New initiatives that attempt to stretch the business model often fall into recognizable patterns, and they typically fail in the same way. Perhaps a company is trying to engage customers in a particular way, or a new service offering keeps getting bolted on to existing products. In any case, failure patterns throughout the organization can help define business realities that are better left untouched.

Jabil, a manufacturing services company, analyzed high-impact decisions, isolating about 20 that were most at fault for downstream strategy issues. The strategy team then trained business unit leaders to spot and avoid these flawed choices.

2. Congruence of Initiatives and Business Value Networks

In “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” Clayton Christensen shed light on a major inhibitor for data storage companies in competing down market: incompatibility of the technologies underlying an incumbent’s success with the emergence of upstarts. When your organization wants to go beyond just adding another product line in the same market, the problem gets exponentially worse. But you may be able to illuminate pending conflicts by comparing sketches of how value is created for the business (such as revenue, learning and experimenting, and heading off competition) and how value is created by the initiative.

Conducting this type of analysis can seem daunting, given the total number of technologies, processes, governance structures and resource types that represent a company’s operating model. You can simplify the effort, however, by bringing in outsiders. Knowledgeable external experts can provide a more unbiased view than stakeholders prone to excessive caution or turf wars.

The chief strategy officer at UnitedHealth Group seeks help from industry experts, customers, suppliers and other value chain partners to assess the company’s capabilities. The diverse set of internal and external perspectives helps challenge ingrained assumptions and balance out conflicts. Getting encouragement to proceed with an opportunity from a broad group of trusted external partners creates tremendous confidence for executives to approve the project.

This article originally appeared in Gartner Business Quarterly in Q2 2021. Download the full issue here.

Experience Gartner Conferences

Join your peers for the unveiling of the latest insights at Gartner conferences.

Recommended resources for Gartner clients*:

Improve Strategic Initiative Success by Considering Risks Throughout Execution

Tool: Strategic Initiative Risk Assessment

*Note that some documents may not be available to all Gartner clients.